Kristallnacht Witness Visits Pascack Hills

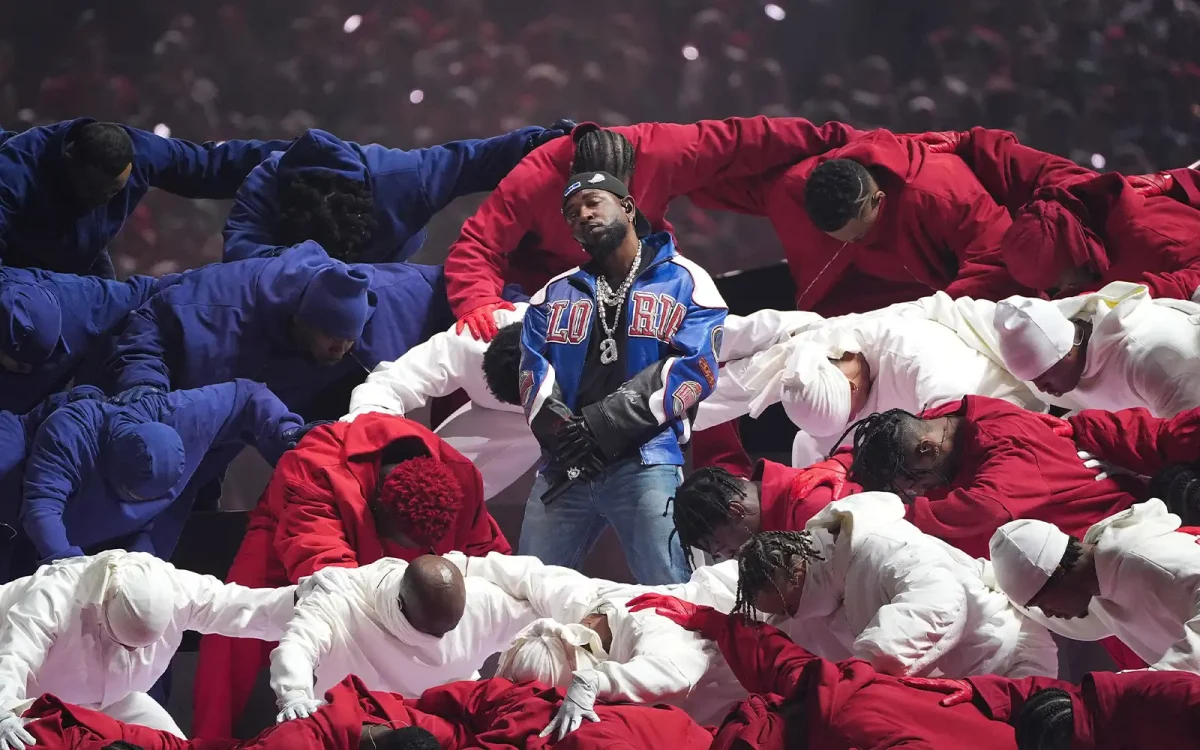

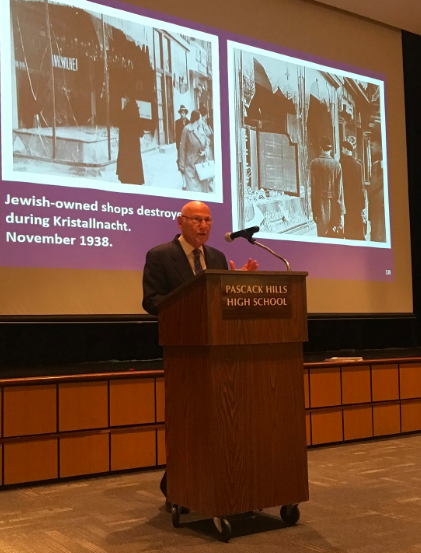

- Erwin Ganz speaking to the Literature of the Holocaust students about the horrors of Kristallnacht.

On Tuesday November 6, Erwin Ganz, a witness of Kristallnacht and a refugee from the Nazi regime, spoke to the Literature of the Holocaust students. He spoke to the students about his childhood in Germany, his experiences during the Nazi regime, and how he and his family escaped to America before they could be deported.

Literature of the Holocaust teacher, Heather Lutz, opened with a short speech to her students, reminding them about the themes they had explored thus far such as culpability and how people can “turn their faces away from the suffering of others.”

Ganz began saying, “This is the story of a boy who was living in Nazi Germany during the two days of Kristallnacht. This boy escaped to America to get away from the Nazi regime. I was that boy and this is my story.”

Ganz was born in Frankfurt, Germany and lived with his mother, his father, and his brother. His father was a banking executive and worked hard to support the family during a time of heavy inflation. Ganz even said the inflation was so bad that you “needed an entire wheelbarrow of money to buy a loaf of bread.” Then, the Nuremberg Laws were placed into effect, which were a series of anti semitic laws that ostracized the Jewish population of Germany socially, economically, and culturally. One of the laws was the Jews were barred from working in civil service or a government-regulated field, so Ganz’s father lost his job.

When Ganz was five, he and his family moved to Bernkastel-Kues to live with his grandmother Emma Lazarus. She owned a small clothing store and his father worked there with her. Ganz was enrolled in the local public school in Bernkastel-Kues, but the school system denied him due to the Nuremberg Laws preventing Jews from attending public schools. So, he was instead enrolled at a Jewish school in Wittlish, 35 miles away from his home.

“I rode 35 miles on the train by myself everyday, and I was only five years old,” Ganz said.

Ganz showed the students his train pass that he kept from all those years ago and explained the difficulties of commuting by himself every day. Each morning and afternoon, his mother would pick him up from the train station. During the time in between, he and other Jewish passengers were subjected to harassment by the Hitler Youth Group while the police turned their backs and did nothing.

Ganz attended school in Wittlish until he was eight years old, and the situation in Germany only escalated. Jewish men were dragged from their homes and beaten in the streets in broad daylight. Jewish businesses further suffered as Germans were barred from purchasing from Jewish stores. The word “Jude” (German for “Jew”) was even spray painted on many Jewish-owned businesses. It was also around this time that deportation began, starting with Jewish men. Fearing the situation and wanting to protect his family, Ganz’s father fled to the United States the night before he was scheduled to be deported.

“Every night, my father would come into my room and kiss me goodnight,” Ganz recounted. “One night, I remember that he kissed me and talked for longer than he normally would. He told me that he would always love me. The next morning, he was gone.”

Ganz’s father immigrated to America that night in order to be able to find work and bring his family over. During the 1930s, immigrants needed a U.S. citizen to sponsor them in order to insure that they would be able to work and contribute to the country. It was difficult, considering that 67% of Americans in 1938 did not want political refugees in the country. Luckily, a cousin supported Ganz’s father and his father strived to earn enough money to bring his family to America.

The situation in Germany truly escalated on November 9, 1938, the first day of Kristallnacht. The day started off normal for Ganz, but he knew that something was wrong. He vividly remembers that the sky was gray and overcast on that day. It was when his mother picked him up from the train station after school that he realized something was truly wrong.

“My mother was waiting there for me holding a banana, which was considered a delicacy at the time,” Ganz said. “She gave it to me to distract me from the horrors in front of me. I will never forget that sight as long as I live.”

Ganz’s house was ransacked by the Hitler Youth Group while he was at school. The windows and mirrors were smashed, paintings were destroyed, the boiler was chopped to pieces, and there were deep hatchet marks in the door frames.

That night, Jewish businesses were raided by Nazis. The shops were destroyed and burned to the ground. All of the windows were smashed and broken glass littered the street. Emma Lazarus’s store wasn’t spared and suffered the same fate. The only synagogue in Bernkastel-Kues was burned to the ground and men were rounded up to await deportation to concentration camps. Jews were also forced to turn in all valuable monetary assets over to the Nazi regime.

Ganz’s father was being updated about the situation in Germany. Since letters and other forms of communication were heavily censored by the government, Ganz’s parents created a code to communicate with each other. When there were good days, Ganz’s mother would snip a lock of Ganz’s hair and send it to his father to let him know that things were all right and the family was safe. Letters without a lock of hair meant that the situation was worsening. Finally, Ganz’s father saved up enough money and he brought Ganz, his mother, and his brother over to America in 1938. They lived in Newark, New Jersey and he considered himself to be an American citizen.

He also told the students a few stories about his multiple trips to Germany and how they affected him. His first trip was about forty years after arriving in America. He travelled to Bernkastel-Kues to visit his old house and see how the town had changed. He visited his old home and saw that the hatchet marks were still engraved in the door frames. He also visited Whittlish to see what had happened to his old school. His school was no longer there and was replaced by a Jewish heritage museum. There were also no longer any Jews living in Whittlish either. Ganz met with the curator of the museum, not telling him that he used to attend school where the museum now stands. The two of them talked about the events in Germany, and Ganz was surprised about the way that the curator had spoken about Kristallnacht and the Holocaust.

“He talked about what happened as if it were thousands of years ago,” Ganz said.

His second trip was an invitation to attend an event in Frankfurt to absolve the town of its guilt. He was one of twenty-five Jews invited to the event who had been born in the town. They took a tour of the town and Ganz was able to revisit his family history. When the group visited the Frankfurt cemetery, he saw that most of the gravestones had been destroyed and remained that way ever since that Nazis had stolen the metal from the stones decades ago. Ganz was surprised when he saw a brick wall in the cemetery. The wall was made of brass bricks engraved with the names of all of those who had died in Frankfurt by the Nazis’ hands.

He was also invited to speak at a high school in Frankfurt about what the German government had done to its own people, stripping them of their rights and systematically killing them. He warned them about the past to prevent such tragedies from happening in their own lifetimes.

“You are the future,” Ganz said to the Frankfurt students. “You must resist all discrimination so what happened to me won’t happen to them.”

Students were given the opportunity to ask Ganz questions at the end. They ranged from more about his past and experiences to his thoughts about anti-Semitism today.

Senior Talya Knopf asked about his struggles about coming to America and adjusting in a new country. She also asked him whether he considers Germany to still be his country or not.

“My country is America,” Ganz replied. “It saved my life and I would do anything it asked of me.”

More students in the audience asked questions about the future of the world.

“Do you think that Kristallnacht can or will happen again?” another student asked.

“What can we do to prevent the current political climate from becoming so severe that it reflects the past?” one student had asked.

The 90th anniversary of Kristallnacht is November 9, and Ganz’s story served as a way to remind the students about what happened in the past and the acts of anti-Semitism being perpetrated today. Lutz had summarized the importance of Ganz’s story and lessons about humanity and empathy well in her opening speech.

“It is up to you- the inspirational, caring young adults sitting in this room, who are interested in learning about the Holocaust and motivated to remember the past and not repeat the future. The time to do so could not be more significant.”

Matt is a senior and this is his second year as the In-Depth editor for The Trailblazer. Matt is excited to lead writers into hard-hitting journalism and write exposés. Although he’s sad his time is ending soon, he knows that his proteges will do well, but until then, he is ready to teach them all he knows!