Cowboys mascot removed, but gender inequity remains at Hills

While the mascot change may be seen as a step towards making Hills sports inclusive of everyone, the work does not stop there.

According to guidelines, both football and cheerleading hold the same risk when it comes to exposure to the coronavirus. But according to state regulations for winter sports, cheer teams are deemed non-essential at basketball games.

As the weather changes, so do the sports seasons. For many students, athletics is an everyday part of life that helps keep them active, social, and healthy. Pascack Hills’ student-athletes dedicate hours to becoming the best versions of themselves in order to compete at the highest level possible.

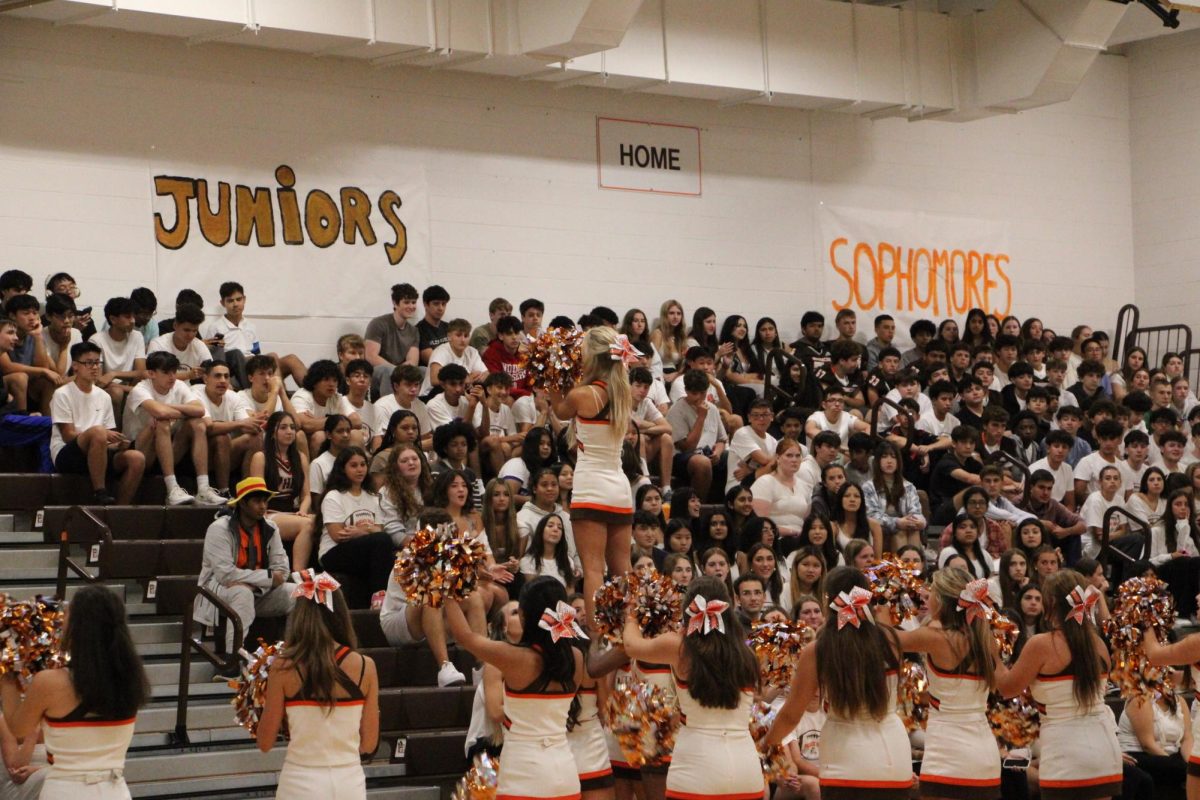

To high school students, sports are a huge part of social culture. Before the pandemic, Friday night football games saw the stands packed with students of all grades and backgrounds, and during pep rallies, the hallways were a sea of brown, orange, black and white.

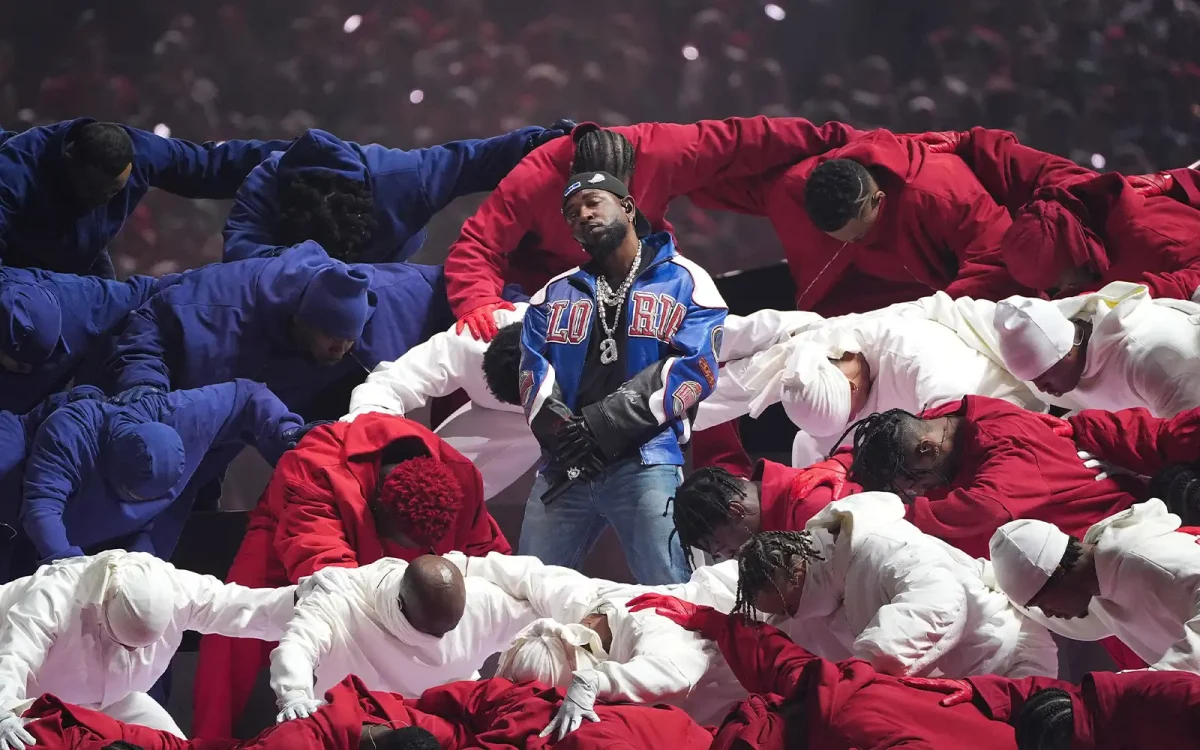

But a large part of a school’s athletic identity is the mascot one plays for, and after much controversy, Hills has moved away from its Cowboys mascot in order to promote inclusion and equity.

Women have long struggled with fighting for their place on the sports field. And while a cowboy doesn’t exactly hold negative connotations, the lack of representation smarts when women in sports have come so far.

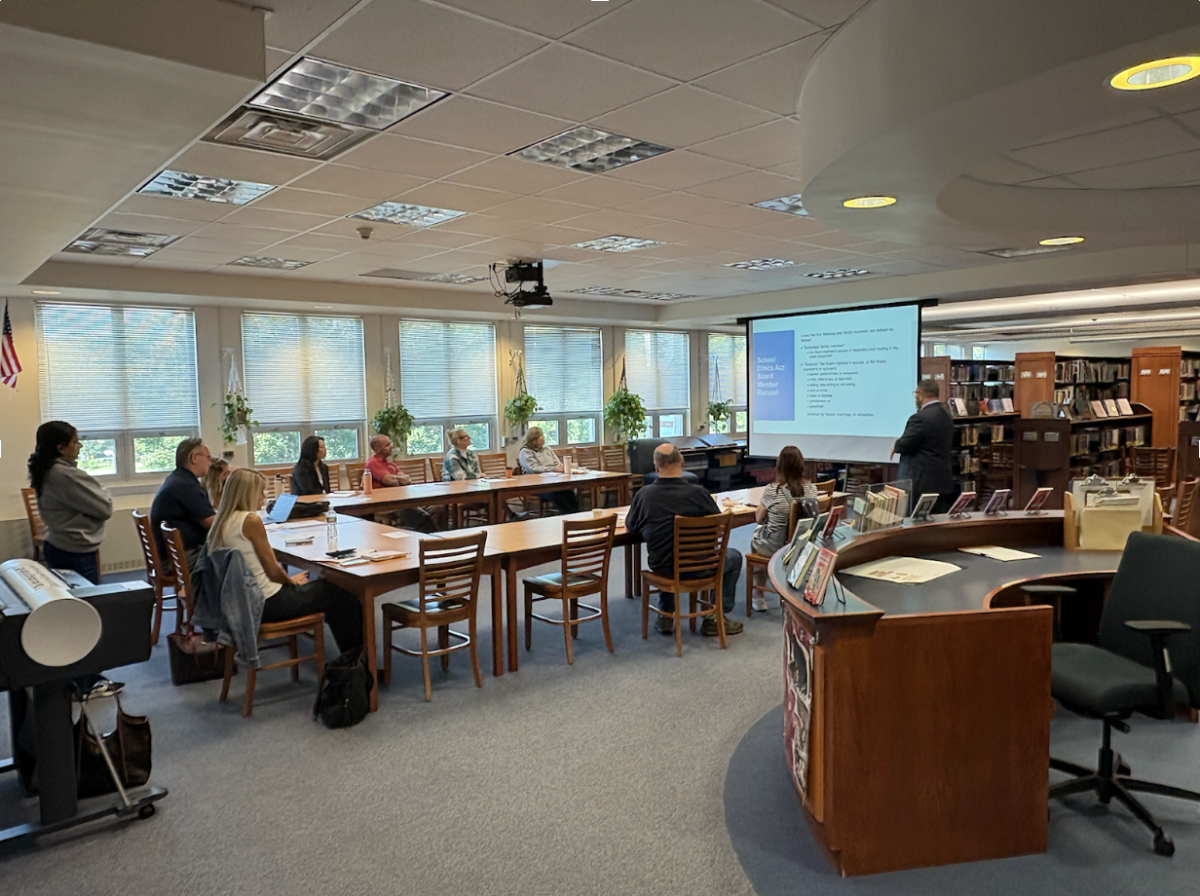

“Much of the gender equity push in our district is based on the survey responses from both the kids and the adults in the building,” said Charleen Schwartzman, who became assistant principal this school year and was one of the administrators who advocated for the Board of Education to change the district mascots. “There is work to be done; through that process, there will be times to reflect on what was accomplished and what still needs work, and I am honored to be a part of that process.”

As of March 8, the Hills mascot has been changed to the Broncos. A bronco is a wild or untrained horse of any gender or breed, with a tendency to buck. While this change may be seen as a step towards making Hills sports inclusive of everyone, the work does not stop there.

“There’s definitely favoritism towards the boys’ teams among the faculty but also among the students,” said Shannon Goodwin, an accomplished senior soccer player who not only led the girls’ soccer team last season in goals but was also nominated for 1st Team All-County. “We see it in the announcements, in the field time.”

When Goodwin says “field time,” she is talking about the turf field that the football and soccer teams have to share during the fall season. Although the time is supposed to be evenly split three ways, the girls’ soccer team seems to fall into last place in the order of importance.

Announcements are also biased according to some students, who say that major achievements by female athletes and teams sometimes go unsung and mostly unknown.

“The board in the gym with all the records hasn’t been updated for girls’ cross country since my freshman year,” stated Sylvie Najarian, Hills senior cross country and track star.

[Update: Athletic Director Phil Paspalas confirmed that the cross country board was updated over the summer of 2020.]Najarian was part of the relay team that set a school record for the distance medley relay by 11 seconds in January 2020. Despite this amazing victory, the achievement was relatively unknown due to a lack of announcements from the school. Spreading awareness about accomplishments is one of the most important parts of full inclusion in athletics, and female athletes are often pushed to the sidelines.

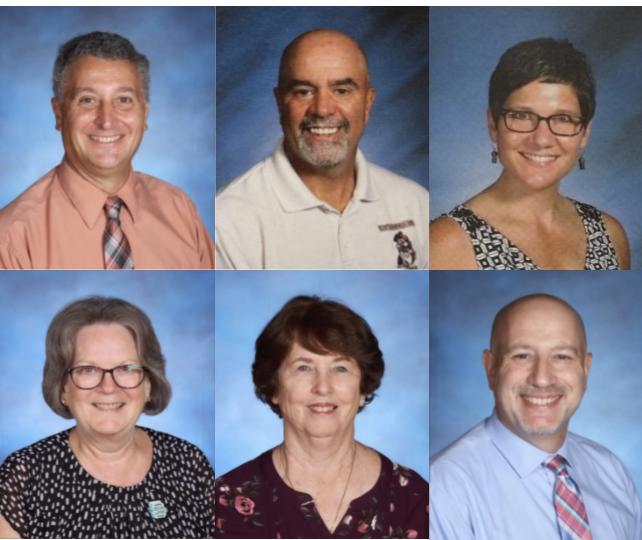

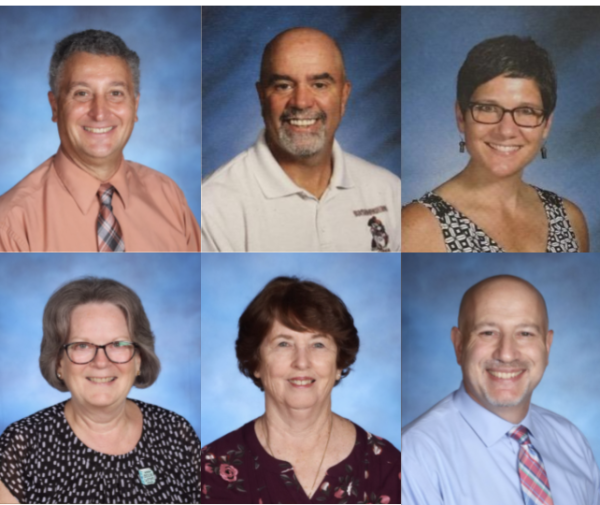

The majority of girls’ teams are coached by men. In fact, there are only four female head varsity coaches at Hills. Out of the 25 total head coaching positions listed on the Hills website, 16 are filled by men and 9 by women.

Although coaching can be done by anyone, female athletes have talked about how having a coach of the same gender has made them feel more comfortable.

“I love having a female coach,” said Goodwin. “It’s different being able to talk to someone who understands more of your problems. [Coach] Brianna Musco is a great mentor and the whole team loves having her as part of the staff.”

There are certain things female athletes would rather not talk about with male coaches. By having a trusted female coach on staff, there is a whole new level of communication opened up, helping both the mental health of the players and their level of play.

Musco, the assistant coach for the girls’ varsity team, is a former Hills soccer player. During her career at Hills, she was awarded 1st Team All-Conference three times, as well as 2nd Team All-County. Musco was also an accomplished basketball and softball player, earning All-County awards in both sports.

It is evident that there are women who are more than qualified to hold coaching positions, but for some reason aren’t being hired for them. At the collegiate level, women only hold 40.8% of head coaching jobs and 49% of assistant coaching jobs. And that is just for the women’s sports team.

Women hold a mere 3% of coaching positions on men’s teams and 11% of all Division I athletic director positions. These statistics are worrying in the fact that there are plenty of women out there who love sports, would love to dedicate their lives to coaching them, and are being pushed aside in favor of men to coach women’s teams.

These are all issues, and they stem from one problem – the fact that female sports are viewed as less than their male counterparts. This phenomenon starts from the bottom and worms its way up, and it is one that is present here at Hills.

“It upsets me when I come in contact with people who don’t take cheerleading seriously,” said Alexandra Pfleging, cheerleading coach and English teacher at Hills. “Cheerleaders throw each other up in the air and have to catch them, risking serious injury. However, we live in a society where there are some who would rather objectify and sexualize cheerleaders instead of acknowledging the athletic skills they possess.”

Competitive cheerleading has one of the highest injury rates in all of athletics, second to only football. Yet there’s still debate over whether cheerleading should even qualify as a sport. How can something so dangerous and physically exerting not even qualify?

One answer is apparent –– its participants are mainly female.

This consistent looking down on female sports has even bled into Covid-19 regulations. Throughout the pandemic, measures have been being taken to ensure that athletes remain healthy and safe while playing their sports. However, the standards for men and women seem to be different.

According to the official New Jersey guidelines, both football and cheerleading hold the same risk level when it comes to exposure to the coronavirus. One would expect that the standards for both, therefore, would be exactly the same.

However, according to New Jersey regulations released for winter sports, cheerleading and cheer teams are deemed non-essential at basketball games. At the time, Athletic Director Phil Paspalas fought for a solution that would allow the cheerleaders of Hills to do what they love in the form of a competition team, but there seemed to be no luck.

Perhaps the reason that girls’ sports seem to be weighed unequally is the fact that having female athletic teams was not legally enforced until 1972 and the passing of Title IX. Title IX states that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Title IX applies to athletics in three different categories: participation, scholarships, and other benefits such as equipment, coaching, and more. Equal opportunity for males and females to play was something that was not enforced before the passing of this law, and since then the number of women in sports has increased by over 500%.

The history of women in sports is one filled with struggle. While men have stood on the field since the beginning of time, women have been fighting on the sidelines to even get a chance to. This time gap between the establishment of male and female sports presents a desperate game of catchup, as females fight to build their athletic programs up to the same level as the men.

For the past two school years, one of the district’s goals has been to “advance the work of inclusivity and equity.” Equity is defined as fairness and freedom of bias, but it seems as though bias unconsciously bleeds into everyday actions.

Hills can be a truly equitable place. Yet, this means that the community needs to take a step back and look at the differences between its male and female athletics, and ask: What can we do better?

Izzy Frangiosa is a senior who has been a part of the Trailblazer since her freshman year. Although she enjoys writing articles of all kinds, she is extremely excited to take over the Sports Editor position with Jacob Charnow. She's ready to bring her passion for athletics to the Trailblazer!

Fun fact: Frangiosa is an avid softball player and CrossFitter.