*Editor’s Note: The following is an op-ed piece.

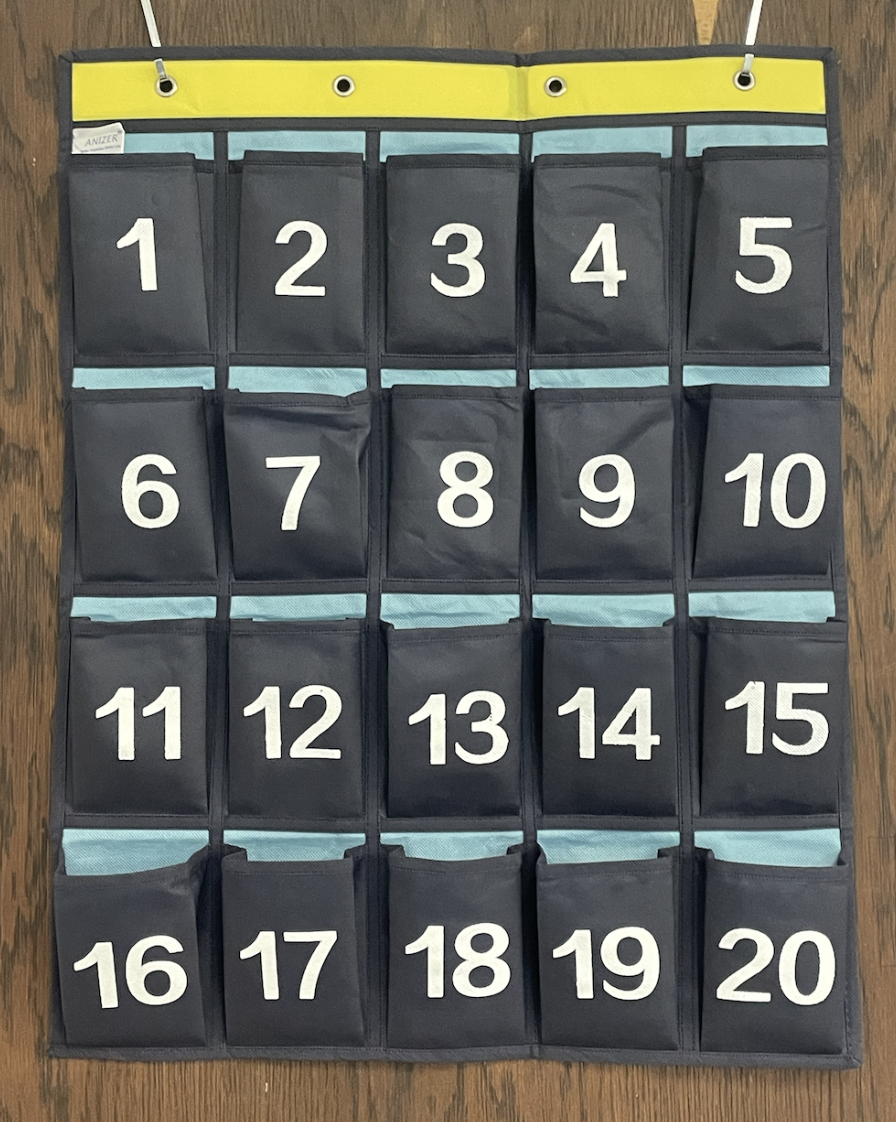

There is a line to be drawn between innovation and reality. How far is too far when it comes to fixing what isn’t broken? The Pascack Valley Regional High School District recently implemented the first formal Open Classroom curriculum at Pascack Valley High School. The initiative, headed by Matthew Morone, involves a non-linear curriculum that “veers away from the unidirectional tendencies of the traditional classroom.” Students learn in a classroom complete with couches, ottomans and even a diner booth—a setting that appears more like a lounge than a classroom.

The Open Classroom promotes an individualized demonstration of skills otherwise learned in a traditional classroom. “Mastery” of common skills such as literary readings and criticisms, argumentative writing and presenting must be met—but in the least common of ways and with the most laid-back of deadlines. Students must present the year’s completed work any day before June 17th.

In a district consistently praised for its promotion of innovation, inquiry and individuality, the goals of the Open Classroom Initiative seem to parallel the district’s vision for learning: encouraging a school climate that “[cultivates] the skills needed to compete and collaborate as ethical and responsible global citizens.” But how do we define responsibility and how can we best prepare our students to take on the responsibilities of the real world? At what point is it just innovation for innovation’s sake rather than for the benefit of the students’ future?

While adhering to the epidemic of stress in schools, this innovative method may be a short-term solution to a long-term issue.

Commenting on the benefits for the multidimensional student, Morone says, “It would make sense for football players to have a lighter load in the fall. [The Open Classroom] enables students in the school musical, in clubs, or with a job to adjust their priorities.” This counteracts the beauty of high school sports and activities: learning to balance multiple commitments in a safe and experimental environment. Agreed; students these days are overwhelmed by their various obligations. However, it is doing a disservice to this generation to soften the influx of responsibilities rather than provide helpful solutions as to how to better deal with them.

Morone admits, “On paper, it can seem like, ‘Oh, wow, they just walk in and it’s this open, super low-stress environment with a ball pit…’” This, he argues, is not the case. Instead, the Open Classroom intends to instill in its students the responsibility of managing their own time—a skill, Morone argues, which can be “even more stressful than the average deadline.”

Morone makes an excellent point; time management is a vital skill. However, it is the combination of this skill and the skills imparted by the traditional classroom setting that will result in a generation that is informed and well prepared for their future.

As businesses and corporations continue to move away from top-down, hierarchal structures, employees are beginning to receive more freedom in managing their own time. While school systems must recognize and adhere to these changes, they mustn’t forget the basic skills that even the most tangential of jobs require: deadlines, obedience and structure—all of which, in the most traditional sense of the terms, the Open Classroom may fail to instill.

Lara Kanjo, a Senior Manager at Ernst and Young, one of the world’s leading professional service organizations, works in a client-serving business.

“My requirement is to provide a high quality service to my clients,” Kanjo says. “I need to make myself available to them and be able to meet their needs at any point in time.”

This reverts back to the necessary parallels between the school system and life post-academia. Figuratively, the directions to a problem are a boss’s orders; an essay’s due date is an invoice’s deadline; the teacher is a demanding client. The goal of an education system is less about the specific content introduced and more about the skills we learn to properly handle such content.

When asked about the characteristics major companies like Ernst and Young look for in potential hires, Kanjo says, “It is important for students joining the workforce to be able to multitask. At any point in time, there will be several things they are asked to do, like completing deadlines and priorities, which they will need to know how to manage.”

The Open Classroom allows for students to spread out their workload. If they do so efficiently, a student may never be working on two things at once. While this seems ideal for lessening stress in the short-term, a student who is not properly experienced in balancing multiple commitments may not be equipped with the tools to thrive in a traditional job setting.

Further, the Open Classroom poses an interesting comparison between the importance of managing our own work and time and the necessity of knowing how to follow a distinct deadline in response to authority. It is finding the balance between the two that will allow this district to thrive as it does.

Dr. Barry Bachenheimer, PVRHSD Director of Curriculum, Instruction and Assessment says, “The intention always is: what is best for the students.” In regards to the Open Classroom, “We will not know [if it works] unless we try.”

While students, teachers and administrators remain insistent of finding the right answer, it is crucial that we recognize there may never be one answer regarding the best way to educate. Teaching does not have a one-size-fits-all approach.

“Would I want to see an entire district of Open Classrooms? I don’t think that fits for everybody,” Bachenheimer says. “Would I want kids to have the option to experience it? Yes.”

We must continue to innovate, but never settle. We may never find the answer. But for as long as we continue providing our students with options and experiences, the answer will be found for as many students as possible.

For an alternative view, take a look at NorthJersey.com’s article about Pascack Valley’s Open Classroom Initiative.